When Apple introduced PowerPC they also introduced the idea of system-level emulation providing a stop-gap for applications (and ROM) to remain as 68K code for a while. The emulator, written originally by Gary Davidian, introduced some novel features, but wasn't terribly fast – it was a later version made by Eric Traut that introduced us to the term "Dynamic Recompiler" which would become the forerunner of Just-In-Time (JIT) Compilers. It serves as one of only two emulators which use this model.

Update on Hardware

The situation on the availability and price on the MCU hasn't improved much – they're still insanely expensive. I will be honest – I'm not sure what to do there. There are a lot of fairly good options out there with the STM32MP13 probably leading the pack, but none of them have the level of integration that the OSD3358 had. Obviously such a pivot means redoing a lot of work, so you can probably understand my hesitation.

But I did finally (OMG!) get the Zorro-I boards in so I can test this on my (more expendible) Amiga 500+ motherboard. These are also the v0.8 boards I've been sitting on that fix all the remaining issues with the PCB.

Yes, the irony that these are "PiStorm" CPU boards is not lost on me. Sigh…

And completely unrelated, I also got my 49" 4K monitor back for Lego-brick sized gaming. Combined with the Amiga to Component adapters it makes for some gorgeous graphics even if lowres is a little absurd on such a screen.

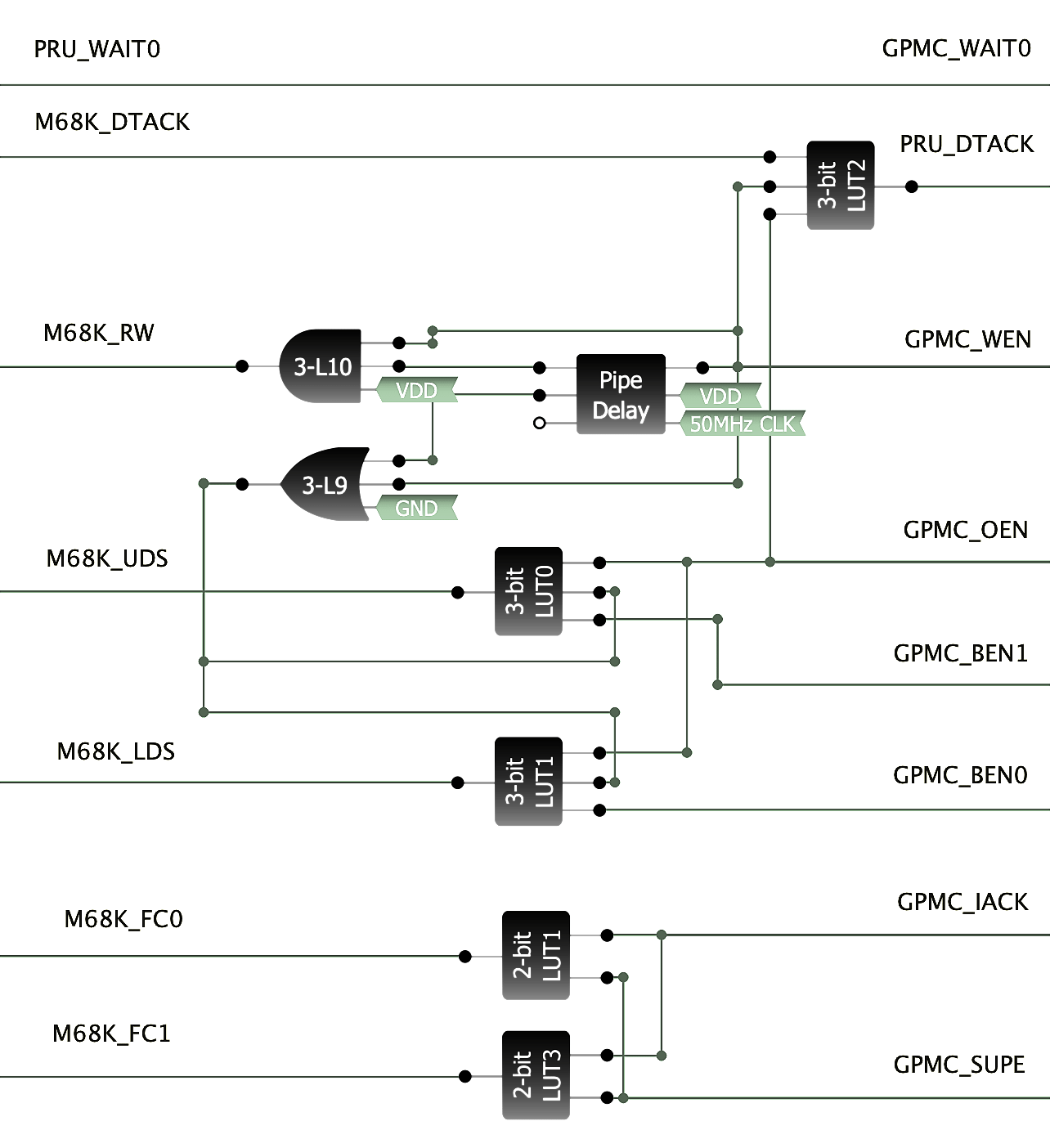

GreenPAK Rework

So I've completely reworked the GreenPAK to essentially eliminate most of what it was doing. It still massages thw R/W, xDS and FCx pins, mostly because the ABSOLUTELY HORRENDOUS LATENCY can be compensated for. But the wait behaviour is completely gone – you can see we're doing nothing but feeding the signal more-or-less RAW to the MCU and back again. More importantly, the MCU itself is now controlling it's own memory controller.

What we're doing is offloading the STUPIDLY SLOW GreenPAK behaviour to the only somewhat slow PRU. This is a RISC coprocessor built into the TI MCUs which is highly deterministic. It nominally works at 200MHz which means we have a 5ns cycle time compared to the 15-20ns delay on the GreenPAK – per function! I've had the PRU clocked up to 333MHz just fine which is a 3ns cycle time – that's a full order of magnitude faster than the GreenPAK. An FPGA it is not, but it's a big improvement.

Okay, maybe some ASCII Art will help here.

AM335x 68K BUS

--------------------.

pr1_pru0_pru_r3x_4 | <-------------------- CLK7

pr1_pru0_pru_r3x_7 | --------------------> ECLK

pr1_pru0_pru_r3x_16 | <-------------------- VPA

pr1_pru0_pru_r3x_0 | --------------------> VMA

| .-----------.

WAIT0 | <-- |12 7 | <-- DTACK

(GPIO_IACK) CSN2 | --> |20 3 | --> UDS

WEN | --> |18 Green 4 | --> LDS

OEN | --> |19 PAK 5 | --> FC0

BEN0 | --> |16 10| --> FC1

BEN1 | --> |17 6 | --> R/W

(GPIO_SUPE) A24 | --> |13 |

| | | 1, 14 Vcc

pr1_pru0_pru_r3x_6 | --- | 2 | 8, 9 I2C

pr1_pru0_pru_r3x_12 | --- |15 | 11 Ground

--------------------' '-----------'

First the DTACK. We do use one gate to basically merge the bus DTACK, as well as the WEN and OEN signals we're emitting from the GPMC memory controller. The logic is rather simple to avoid any more delays than we ABSOLUTELY need to. In this case what we want is for our PRU_DTACK signal to rise when we're in S7 (to synchronize with the bus clock) and fall when the bus is ready (normal DTACK use). The OEN and WEN signals will be used here to signify the S7 state as we can precisely control their timing.

This does put a LOT of extra load on the PRU which originally was just going to be an E-Clock creator. Now in addition to this we need to track CPU states (which are on either edge – so happen twice as fast) and watch for wait states. It's a lot, but I'm making progress. I've ran some tests and I'm back to the point of being able to read ROM fine, so it's only DRAM now.

You might wonder why? Well, simple because the GreenPAK does not have the bus clock while the PRU does. The fact that it might be faster is a bonus, but really, it's about the clock. When we hit our 98% read/write accuracy, the 2% failure was because we'd fall out of phase with the bus clock and perform a read or write while the bus latches were still engaged.

In a nut-shell, our "approximate" clock is not good enough. We must be synchronized to the Amiga's bus clock, perfectly. I don't know if this is an Amiga-ism as the 68000 is "supposed to be" asynchronous, but if it can be made to work there, it will work anywhere.

Firmware Update

I won't hide that PJIT and Apple's DR share a LOT in common. I didn't actually know this at the time though, so it was "clean room". However, knowing this now has helped give me some insight on some critical optimization strategies. We can actually look at the Apple source code for the emulator to see the improvement.

Apple 68LC040 "Emulator"

Interpretive Dispatch Table

lis data, 0x0004

b add_w_shifted_data_d2

Interpretive Semantic Routines

add_w_shifted_data_d2:

rlwimi disp_table, prefetch_data, 3, 13, 28

rlwinm immed_data, d2, 16, 0, 15

mtlr disp_table

addco. data, data, immed_data

lhau prefetch_data, 2(pc)

mfxer ccr_x

rlwimi d2, data, 16, 16, 31

bgelr+ cr2

b process_special_event

Interpretive Code Path: 10~12 cycles (normally)

The Interpretive Dispatch Table was 512KB of basically every 68000 opcode – all 65536 – even the thousands of illegal opcodes – arranged in a pattern of non-jump and jump instructions. The non-jump was a prefix instruction which would attempt to mitigate as much as possible any uniqueness from the common subroutine. Sometimes this was impossible, and a lot of decode work was still done in the common routine – in other cases, the whole 68000 instruction could be emulated in one opcode.

However, these instructions weren't "inline" so a branch was still necessary. In these cases, the IDT would jump to a short sequence which would simply load the opcode and then jump again. This was far from efficient, and Eric Traut solved this with the cache.

The Apple Dynamic Recompiler (DR) improved the emulator quite a bit – in some cases, doubling its speed, and did so without significantly breaking how the former worked, allowing the ROM to switch between emulation and DR mode as necessary.

Apple 68LC040 "Dynamic Recompiler"

DR Cache

lis data, 0x0004

bl dr_add_w_shifted_data_d2

lhau prefetch_data, 2(pc)

bt cr_sp_event, handle_special_event

DR Semantic Routines

dr_add_w_shifted_data_d2:

siwi immed_data, d2, 16

addco. data, data, immed_data

riwimi d2,data, 16,16,31

mixer ccr_x

bir

Dynamically Recompiled Code Path: 6 cycles (normally)

The cache is now organized much like a conventional CPU cache consisting of cache lines – each cache line was comprised of 32 cache line entries with each entry being four PowerPC opcodes. This means a whole CLE is 16 bytes and the whole CL is 512 bytes. When initialized, the whole line would be translated at once.

Every instruction always took four instructions – the first was copied from the IDT, the second was computed from the DR Offset Table that pointed into the DR Semantic Table (a collection of the opcode stubs), and the third and fourth instructions were simply the exact same for every opcode to perform the 68000 data prefetch. In cases where the instruction is 2- or 3-words, the lhau instruction would load from 4(pc) or 6(pc) respectively.

The last instruction would test for interrupt state and branch to the general event handler routine when necessary. Compared to the frequency of instructions, this was a rare event.

In many cases, 68K opcodes would take one, two or three PowerPC opcodes. In these cases they were labelled as "special case" and instead of caching the branch to the DR Semantic Routine, it called it directly and had that routine write the opcode instead. In the special case of three opcodes, a concession was made to not perform the interrupt-check which could cause some extra interrupt latency – something that was acceptable on the PowerMac, but not so much on other platforms like the Amiga.

Buffee PJIT

PJIT Cache

add r1, r5, offsetof(D2) + 2

bl add_w_immediate_4

PJIT Semantic Routines

add_w_immediate_4:

ldrsh r0, [r1]

orrs r0, r0, #4

strh r0, [r1]

bx lr

PJIT Code Path: 3 cycles (normally)

There are a few things here that should jump out if you actually tried reading the PowerPC code (and sorry for that, PowerPC assembly is the worst). We're not at all thinking about interrupts, we're not performing any prefetch and we're dealing with D2 as a memory operation.

M68K Interrupt Handling

The magic here is that we still have and do not disable the interrupt handlers, but instead of doing any actual interrupt handling, all they do is alter the user-mode link register and then return. Now, when the semantic routine is done and the BX LR instruction is encountered, instead of jumping back to the next opcode in the cache, it jumps to the M68K interrupt handler.

This saves us having to do this for every opcode.

M68K Prefetch

PJIT does not emulate the prefetch (albeit with one exception – the RESET instruction), and of course, with PJIT, instead of handling the extension words and data within the semantic routines, these are prefixed within the PJIT cache itself as reversed order of opcodes, so any PC, address or immediate is already in r1 or r2.

This saves us having to do this for every opcode.

Data Registers in RAM

Lastly, because the data registers would overflow our available ARM CPU registers, D2 thru D7 are instead stored in RAM. This may incur latencies depending on where in RAM they're presently stored, but based on its frequency should almost certainly always remain in L1 cache.

However, changing this to D0 does not significantly reduce the number of instructions on either the ARM or PowerPC since neither are capable of working with byte and word values directly. So if this were D0, the sequence would instead be:

PJIT Cache

sxth r0, r3 + Dn

bl add_w_immediate_4_D0

PJIT Semantic Routines

add_w_immediate_4_D0:

orrs r0, r0, #4

bfi r3 + Dn, r0, 0, 16

bx lr

nop

Note that we add a nop to the end to round up the length of the routine. The Cortex A8 uses 64-byte (16 instruction) cache lines, so we want to keep these from causing a single opcode from taking up multiple cache lines. This was one of the good lessons from the Apple DR patent – keep your subroutines cache-aligned.

So why not also use four opcodes? Well, it would allow for far more instructions to be inlined, however, even on the Cortex A8, the branch predictor is robust enough that this seldom matters. Also, unlike the PowerPC version, we have a lot of M68K opcodes that only take one or two instructions meaning that we'd be adding a whole lot of NOPs and there's just nothing to do in those spare slots.

So what about the flip side? Well, just one opcode means we're just always doing a branch. There are plenty of M68K opcodes that can be done in one ARM instruction (including most branches), and it would mean we're never adding NOPs to the cache (except for the NOP instruction), but for all the rest, it does mean always jumping to a specific subroutine handler. This makes the semantic routines rather large – about 2MB or four times the size that PJIT is with it's 512KB opcode table + semantic routines.

One of the other interesting things from the Apple Patents though is the low-energy required to assemble the DR Cache opcodes. It really is elegant having the DR Offset Table and DR Semantic Routines. This means the IDT can still be used directly for interpreter use. However, since we handle extension words quite differently, this had to be adapted somewhat. But the benefit is huge.

New PJIT Structure

PJIT (PJIT Instruction Table) holds the single prefix instruction for every opcode. This table is exactly 256KB and should be aligned to 256KB in memory.

PJSR (PJIT Semantic Routines) holds all the opcode subroutines needed to complete the M68K instruction after executing the prefix operation. This should not require more than 64KB of RAM. The PSR exists and remains entirely in the bootloader SRAM.

PJOT (PJIT Offset Table) holds a 16-bit offset into the PSR with the low two bits indicating the type of routine in the PSR. This should take exactly 128KB of RAM (2x64K).

I'm still ironing out the details and changes to the code, but this is going to make the tables a LOT smaller and this means much more liklihood that they're in cache – this isn't that much larger than the sum of the L2 and L1 caches on our Cortex A8, and that's fantastic.

On A Personal Note

I am very sorry for all the delays. I don't want to get into the details but let's say that getting old sucks. I'm getting better though and I've started to feel a little bit more energetic and getting back into things.

Let's hope 2024 is a better year.

And for anyone still out there reading this, thank you for your patience.